In the late eighteenth century, Britain’s Royal Navy employed small, lightly armed vessels to support its colonial ambitions. One of these craft was the HMAV Bounty, a former collier renamed and refitted to transport breadfruit trees from Tahiti to Britain’s Caribbean colonies. The Admiralty, encouraged by the scientist Joseph Banks, believed that breadfruit would provide an inexpensive food source for enslaved workers in the West Indies. To carry more than 1,000 potted plants, the vessel’s great cabin was converted into a greenhouse, reducing space and leaving the complement of 46 sailors cramped for a voyage expected to last more than two years.

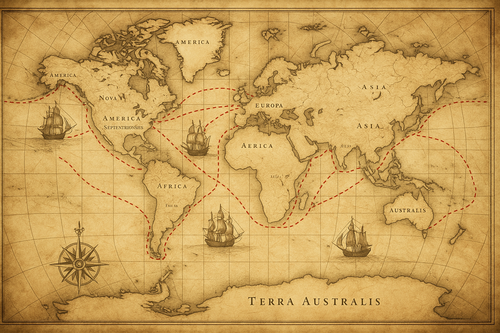

Lieutenant William Bligh, a seasoned navigator who had sailed with James Cook, was chosen to command the expedition. On 23 December 1787, Bounty slipped out of Spithead, Portsmouth and pointed towards Cape Horn. Storms barred passage around the Horn, so Bligh steered eastward and reached Tahiti (then “Otaheite”) on 26 October 1788 after a ten‑month voyage. The crew remained for nearly six months to wait for breadfruit seedlings to mature.. During this layover they enjoyed life on the island, forging relationships with Tahitians and embracing a tropical rhythm far removed from naval discipline. Bligh noted the island’s “paradise” qualities and allowed a relatively relaxed regime while the plants were collected, yet he remained a strict disciplinarian, punishing infractions harshly and reprimanding subordinates for perceived slothfulness. Over time tensions mounted between the captain and several crewmen, including his young protégé, acting‑lieutenant Fletcher Christian.

Discontent and the Road to Mutiny

( Fletcher Christian sets Lieutenant Bligh and 18 crewmen adrift — a moment captured in Robert Dodd’s 1790 aquatint )

The circumstances that provoked mutiny remain debated. Historians cite Bligh’s volatile temper and penchant for public humiliation, the crew’s resentment at leaving Tahitian partners behind, and the general hardship of eighteenth‑century naval life. Historic UK notes that sailors later claimed the captain’s “harsh and cruel” treatment as a motive, though conditions on eighteenth‑century ships were notoriously difficult. The long stay in Tahiti exacerbated this friction: when Bligh ordered preparations to sail on 4 April 1789 the crew were “reluctant to say their goodbyes,” having been beguiled by the charms of Tahitian women and the island’s easy living. Christian himself had formed a relationship and was openly discontented. Some of his later statements blamed Bligh’s insults; Bligh insisted that the men had become ungovernable after tasting Tahitian freedom.

Leaving Tahiti, Bounty headed west toward the West Indies. Less than four weeks later, before dawn on 28 April 1789, Christian and a group of about twenty‐five men seized the ship near the island of Tofua in present‑day Tonga. The takeover, though sudden, was bloodless. Armed with muskets and cutlasses, the mutineers restrained the sleeping captain and loyal crew, then hustled them on deck. Bligh and 18 loyalists were ordered into the 23‑foot launch — a boat intended for short trips between ship and shore. Norfolk Online News records that Christian’s group forced Bligh and his followers to leave without any significant violence. The mutineers provided some food, a sextant and quadrant but no charts or chronometer; the overcrowded boat sat perilously low in the water and offered scant shelter. Historians continue to marvel at Christian’s decision to provide navigational instruments and spare the captain’s life, suggesting that the young officer hoped to avoid murder charges should they one day face British law.

The Open‑Boat Journey

Bligh’s seamanship turned what might have been a death sentence into an extraordinary voyage. Lacking charts, he plotted a course by memory, using a compass and sextant to estimate position. He initially tried to land on Tofua for water but was driven off by hostile islanders; one of his men was killed by a stone during an attack, the only casualty of the ordeal. Realizing that further stops risked violence, Bligh resolved to sail directly to the Dutch outpost at Timor, some 3,600 miles (about 5,800 km) away. In the cramped launch the men subsisted on meagre rations of salted meat and ship’s biscuit. To stave off dehydration they collected rainwater, and Bligh enforced strict discipline, limiting quarrels and maintaining a log and chart.

After 48 days at sea, the exhausted party sighted Timor and reached Coupang (Kupang) on 14 June 1789. The voyage covered almost four thousand miles. Historic UK describes it as a “journey of almost 4,000 miles” accomplished without charts. Only one man had died; the rest survived because of Bligh’s navigation and organisation. From Timor, Bligh sailed to Batavia (Jakarta), then eventually returned to England via Cape Town, arriving in March 1790. In London he faced a routine court‑martial for losing his ship but was acquitted and praised for his handling of the open‑boat journey.

Life Aboard the Captured Bounty

Meanwhile, Christian and his followers debated their next move. Without a commission or safe harbour, they were effectively pirates. They initially attempted to settle on the island of Tubuai, 450 miles south of Tahiti. There they clashed with Polynesian islanders and built fortifications, but after weeks of violence they abandoned the settlement. Returning to Tahiti in September 1789, the mutineers split. Sixteen crewmen either chose or were forced to stay; most were soon captured by a British vessel, HMS Pandora, sent by the Admiralty in 1790 to apprehend the mutineers. The captured men endured a grim voyage back to England, during which Pandora sank on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef with the loss of some prisoners. At their court‑martial three were hanged, three were pardoned and three acquitted.

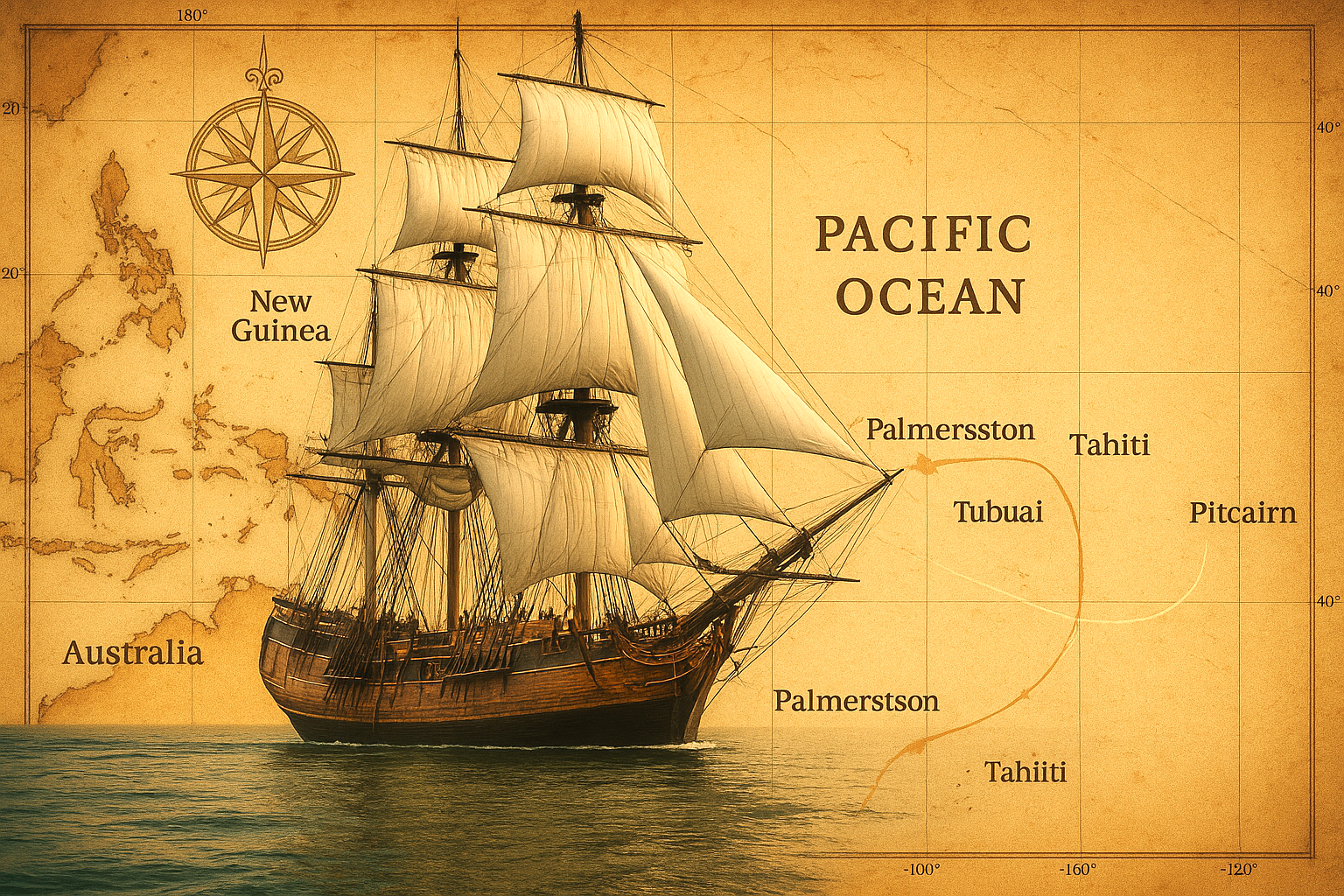

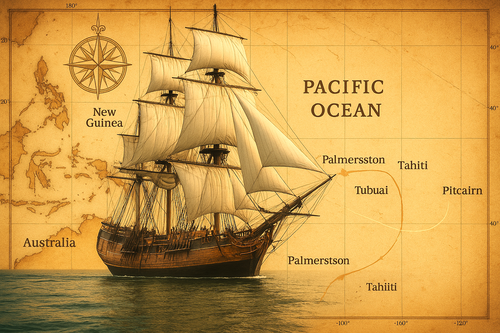

( Map showing Bounty's movements in the Pacific Ocean between 1788 and 1790 )

( Map showing Bounty's movements in the Pacific Ocean between 1788 and 1790 )

RED - Voyage of Bounty to Tahiti and to location of the mutiny, 28 April 1789.

GREEN - Course of Bligh's open-boat journey to Coupang, Timor, between 2 May and 14 June 1789.

WHITE - Movements of Bounty under Christian after the mutiny, from 28 April 1789 onwards.

Christian and eight loyal mutineers refused to surrender. In September 1789 they took Bounty back to Tahiti to acquire provisions and partners. In January 1790 the group — now including six Polynesian men and twelve women — sailed east and eventually reached remote Pitcairn Island. This uninhabited speck was mis‑charted on contemporary maps, offering concealment. To avoid detection they stripped the Bounty of useful materials and burned her in Bounty Bay. There they established a tiny community, intermarrying with the Tahitian women and planting crops. Quarrels and jealousy soon erupted. Within a few years most adult men died violently, either in clashes between Englishmen and Polynesians or in personal disputes. Christian was probably killed around 1793, though accounts vary. By the time an American sealing ship stumbled upon Pitcairn in 1808, only one mutineer, John Adams (born Alexander Smith), was still alive with a handful of Polynesian women and their children. Adams told visitors his tale; Britain eventually pardoned him, and the Pitcairn population grew under his patriarchal guidance.

William Bligh After the Mutiny

The mutiny did not end William Bligh’s career. He returned to sea and in 1791 successfully completed another breadfruit voyage to the Caribbean. Later he served in battles during the French Revolutionary Wars and was made a rear‑admiral. In 1805 he was appointed governor of New South Wales. His attempts to curb the colony’s illegal rum trade precipitated the Rum Rebellion of 1808, during which he was arrested by his own officers and held under house arrest for a year. Despite another mutiny, Bligh was exonerated, promoted to vice‑admiral and died in London in 1817. His later life illustrates a man simultaneously capable of exemplary seamanship and abrasive leadership.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

The Bounty mutiny became an enduring part of maritime lore. Its narrative, balancing tyranny, freedom and survival, appealed to nineteenth‑century audiences. Writers and filmmakers often portrayed Fletcher Christian as a romantic rebel and Bligh as a sadistic martinet. These depictions drew more from Hollywood than historical sources, but they cemented the story in popular imagination. Pitcairn Island’s unusual history — inhabited by a mixture of British mutineers and Polynesian women — inspired novels and genealogical interest. Descendants of the mutineers still live on Pitcairn and on Norfolk Island, where the British government resettled most Pitcairn families in 1856 due to resource shortages.

The case also prompted legal and political debate. Under the British Articles of War, mutiny was punishable by death; the courts that tried the captured mutineers wrestled with issues of compulsion, as some sailors claimed they were forced to join the mutiny. The open‑boat voyage furthered scientific understanding of long‑distance navigation and survival. Bligh’s meticulous logs, preserved by the State Library of New South Wales, reveal his navigational methods and daily rationing. They show that he used a small compass and sextant, measured noon sun altitudes, and kept careful track of latitude and estimated longitude. Modern survivalists study the voyage as an example of leadership under extreme conditions.

Conclusion

The mutiny on the Bounty remains compelling because it illuminates the human dimensions of maritime exploration. It began as a scientific mission to transplant breadfruit and ended in rebellion, exile and legend. William Bligh emerges as both an exceptional navigator and a flawed leader whose abrasiveness contributed to the mutiny. Fletcher Christian appears as a complex figure torn between duty, personal relationships and a sense of injustice. The crew’s months in Tahiti and their longing for island life highlight the stark contrast between imperial service and the appeal of the Pacific. Two centuries later, the story resonates as a cautionary tale about leadership, discipline and the unpredictable consequences of human desires on long voyages across vast oceans.