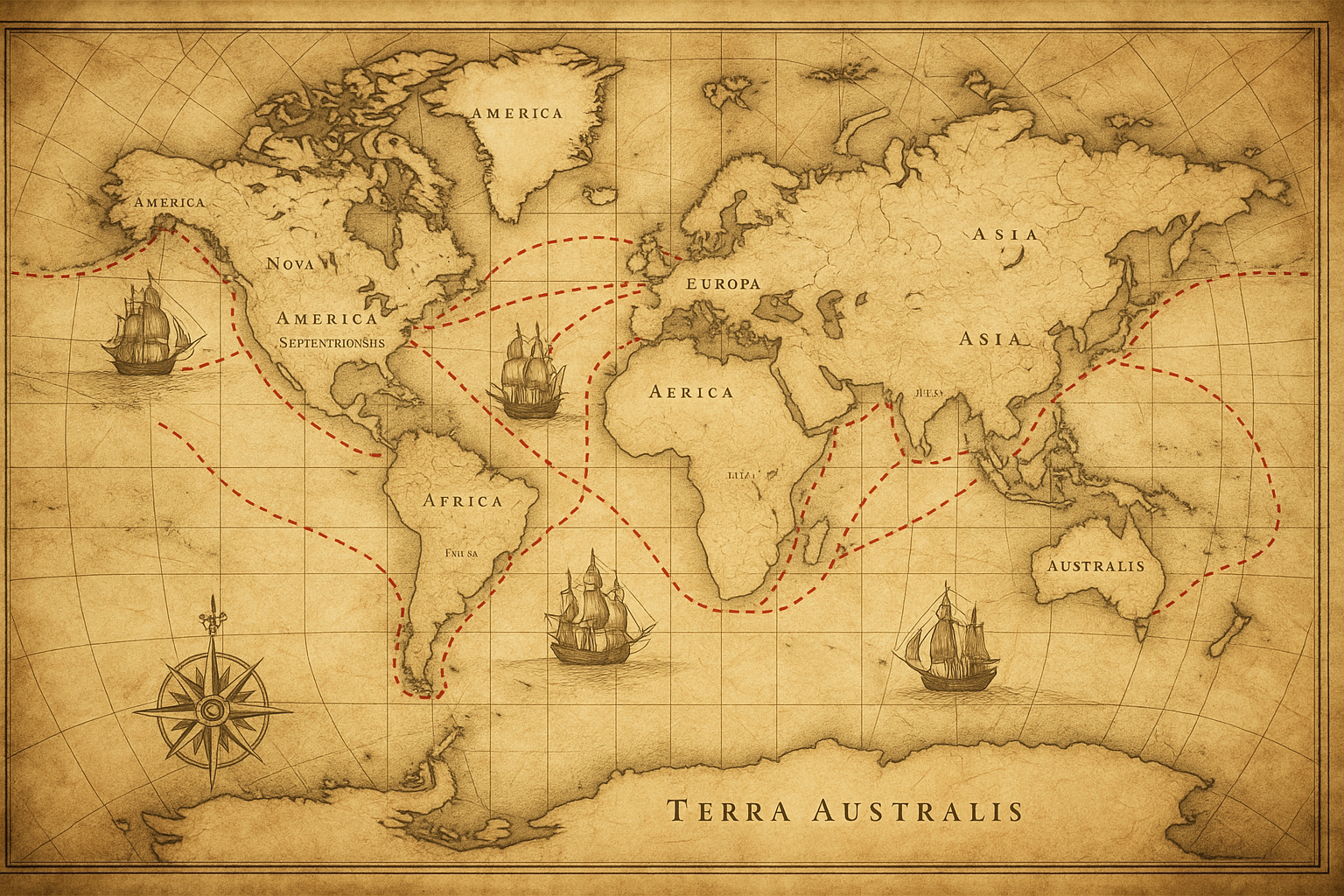

Throughout the early modern and modern periods, the oceans were not simply vast stretches of water separating continents—they were dynamic highways of trade, conquest, and cultural exchange. Nations that mastered the seas often dominated the world stage, projecting power far beyond their borders. Central to this maritime supremacy were two types of ships that symbolized different stages of empire-building: the sturdy, heavily armed East Indiamen and the fast, elegant opium clippers. These vessels were far more than mere tools of commerce; they were instruments of geopolitical transformation, carrying goods, soldiers, ideas, and ambitions to distant shores. From the spice markets of the East Indies to the tea fields of China and the opium dens of Canton, the East Indiamen and the opium clippers helped forge a new world order, laying the foundations of the modern global economy.

The East Indiaman: Merchantman, Battleship, and Empire-Builder

The story of the East Indiamen begins in the early 17th century, as European powers raced to secure their share of the riches of Asia. Companies like the British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company were chartered to monopolize trade with India, China, and the islands of Southeast Asia. However, simple merchant ships were ill-suited to the perils of long voyages through pirate-infested waters and rival colonial navies. The response was the creation of the East Indiaman—a ship uniquely crafted to balance the needs of commerce, defense, and endurance.

East Indiamen were enormous by the standards of the day, often displacing between 800 and 1,200 tons. Their size allowed them to carry vast quantities of precious cargo, including silks, spices, porcelain, and later tea. Yet these ships were also floating fortresses, equipped with rows of cannons and manned by large crews trained to repel attackers. Their sturdy construction and impressive armament made them a formidable presence on the seas, capable of defending themselves against pirates or participating in fleet actions when required. The East Indiamen were not only vital to trade but were integral to the very process of empire-building. Wherever they went, they established commercial beachheads that evolved into political and military strongholds. In India, for example, trading posts at places like Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta, initially founded to serve East Indiamen trade, grew into colonial cities that became essential parts of the British Empire. The economic wealth generated by the East Indiamen’s voyages funded the private armies of the East India Company, which in turn facilitated territorial expansion and consolidation.

The voyages themselves were monumental undertakings. A typical round trip from London to India or China and back could take two years, with stops at remote islands like St. Helena or Mauritius for resupply. Navigating such distances required immense skill, resilience, and courage. Crews faced storms, disease, shipwrecks, and hostile encounters. Yet the potential profits were so extraordinary that merchants and investors were willing to accept the high risks.

Transforming the Global Economy and Cultures

The East Indiamen did not merely carry goods; they carried transformation. They connected Europe with the wealth of Asia and helped integrate distant regions into a single, albeit unequal, global economy. They introduced European manufactured goods into Asian markets and returned with exotic products that would become central to European life. Spices revolutionized cuisine, tea reshaped social rituals, and Chinese porcelain and textiles influenced European tastes and fashions.

However, the exchanges were rarely balanced or benign. Indigenous economies were often upended by the influx of European products. Local crafts and industries declined as European goods displaced them, and traditional power structures weakened under the weight of foreign economic influence. Moreover, the growing wealth disparity between European nations and their trading partners contributed to an imbalance that often paved the way for direct colonial rule. Commerce was frequently backed by military force, and treaties were often negotiated at the point of a cannon. Culturally, too, the impact was profound. Missionaries traveled alongside merchants, spreading Christianity to new lands. European political and legal ideas seeped into colonial administrations, altering indigenous governance systems. Yet the cultural flow was not entirely one way. Asian art, philosophy, and even medical knowledge influenced European thought, albeit often filtered through orientalist interpretations.

The Age of the Clippers: Speed, Risk, and the Pursuit of Profit

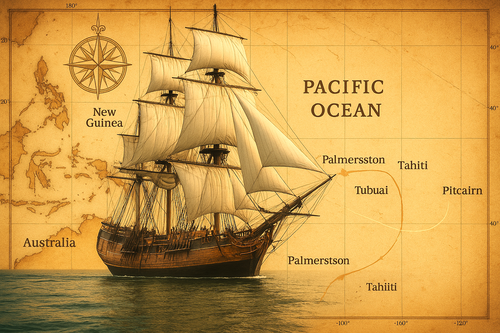

By the early 19th century, the maritime world was changing. The old, heavy East Indiamen, while reliable, were increasingly seen as slow and cumbersome in a rapidly evolving global economy. As demand intensified for faster delivery of goods, particularly perishable and high-value commodities like tea, a new breed of ship came to dominate the high seas: the clipper.

The clipper ships represented a revolution in ship design. With their narrow hulls, towering masts, and vast expanses of sail, they were built for one purpose—speed. Capable of crossing oceans at breathtaking velocities, clippers became the vessel of choice for merchants willing to trade cargo space for rapid passage. They cut journey times dramatically, allowing goods to reach markets while still fresh and allowing merchants to gain competitive advantages in volatile markets. One of the most notorious uses of clippers was in the opium trade between British-controlled India and China. By the early 19th century, Britain's insatiable demand for Chinese tea had created a massive trade deficit. In an effort to correct this imbalance, British merchants began exporting Indian-grown opium to China, despite Chinese laws banning the drug. The opium clippers played a central role in this trade, carrying their illicit cargo with speed and stealth, often eluding Chinese patrols. The profits from the opium trade were immense, enriching not only merchants but also funding further imperial ambitions. Yet the social cost to China was catastrophic. Opium addiction spread rapidly through all levels of Chinese society, leading to widespread social decay and public health crises. The Qing government’s efforts to suppress the trade ultimately resulted in open conflict with Britain.

The Opium Wars: Commerce Enforced by Cannon

When Chinese officials seized and destroyed British opium stocks in Canton in 1839, Britain responded with force. The resulting First Opium War revealed the vast disparity in military power between the two nations. Britain's modern navy, supported by steam-powered gunboats and experienced naval commanders, easily overwhelmed Chinese defences.

The war ended in 1842 with the Treaty of Nanking, which imposed harsh terms on China. Hong Kong was ceded to Britain, five treaty ports were opened to foreign merchants, and significant reparations were demanded. Trade barriers fell, and Western influence in China grew exponentially. The victory cemented Britain's dominance over Chinese trade for decades to come. The role of the opium clippers in this story cannot be overstated. They were not just traders; they were the vectors of an imperial strategy that combined economic exploitation with military coercion. The clipper ships symbolized the aggressive new phase of European imperialism, one that relied less on establishing slow-growing colonial settlements and more on asserting direct control over foreign markets and societies.

The Decline of Sail and the Legacy of Maritime Empires

The golden age of the clipper was relatively short-lived. By the mid-19th century, technological advancements heralded a new era of maritime power. Steamships, no longer dependent on the whims of the wind, could maintain strict schedules and carry larger cargoes. The construction of the Suez Canal in 1869 further favored steam over sail, shortening the journey between Europe and Asia and rendering the traditional clipper routes obsolete. Iron and later steel hulls replaced wood, and maritime commerce became increasingly dominated by vast steamship lines. The once-glorious East Indiamen and the sleek opium clippers faded into history, their designs rendered impractical by new demands for efficiency and reliability.

Yet their legacy endures. The global economic networks they helped establish continue to shape modern trade patterns. The cities they helped found grew into some of the world’s great metropolises. The cultural exchanges they initiated—often unequal and contentious—continue to resonate in complex postcolonial societies. The world they built was one of profound inequality but also unprecedented connectivity, setting the stage for the intertwined global civilization we inhabit today.

Ships as Instruments of History

The East Indiamen and opium clippers were not just marvels of maritime engineering. They were the very mechanisms by which empires expanded, dominated, and exploited the world. Through them, oceans were no longer barriers but thoroughfares of conquest and commerce. They carried soldiers and traders, missionaries and settlers, goods and ideologies, forging connections across oceans and continents.

Their stories are reminders that technology is never neutral. Ships designed for commerce can become engines of conquest. Trade can be a means of cooperation, but also a tool of subjugation. As we navigate the complex legacies of globalization today, we would do well to remember the towering masts and billowing sails of the East Indiamen and the opium clippers—the ships that built, and sometimes broke, empires.