A Unified Iberian Maritime World

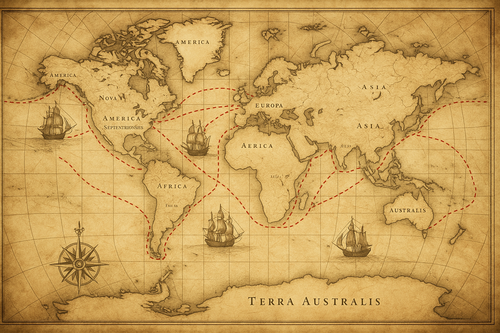

The Iberian Union (1580–1640) joined the crowns of Portugal and Spain under the Habsburg monarchs. Although the kingdoms kept separate administrations, the union integrated two of the world’s largest maritime empires and temporarily pooled resources, fleets and territories. The period coincided with the second phase of the Age of Discovery, when rival maritime powers – notably the Dutch and English – began to challenge Iberian dominance. The union’s maritime history is therefore one of ambition and adversity: Iberian galleons carried silver and spices across oceans while new competitors attacked them; the Philippines and Brazil flourished as colonial hubs, yet the costs of war and economic mismanagement weakened the empire. This article examines the Iberian Union’s maritime history between 1580 and 1640, focusing on ship types used for trade and war, the trade networks linking Europe with Asia and the Americas, and the exploration and conflicts that shaped the period.

Ship Types Used in Trade

Caravels and Round Caravels

The caravel had been the workhorse of Iberian exploration in the fifteenth century. It remained important during the union for coastal reconnaissance and light cargo. Caravels were relatively small (50–60 tons), with a shallow draught that allowed them to explore rivers and coastlines. They carried two or three masts with lateen sails that could tack against the wind, giving them great manoeuvrability. By the late sixteenth century, caravels evolved into round caravels that weighed up to 300 tons, sometimes carrying four masts and mounting cannons for defence. These larger caravels became the forerunners of the galleon and were used in colonial waters such as Brazil and Guinea.

Naus (Carracks)

For transoceanic trade the Portuguese and Spanish relied on the carrack, called a nao in Portuguese. Carracks had two or three masts rigged with a combination of square and lateen sails, high forecastles and sterncastles, and a deep, wide hull that provided stability and enormous cargo space. Early carracks weighed around 250 tons, but by the sixteenth century they grew to 1 300–2 000 tons. Their design blended Mediterranean and Northern European practices: lateen sails allowed sailing to windward while square sails provided power on long ocean crossings. Carracks were true multirole ships: they served as cargo carriers and, when armed with cannons, as warships. Their large size made them suitable for the India Run, carrying spices, silks, and porcelain from Asia to Lisbon, and they supported the Manila galleon trade between Mexico and the Philippines.

Galleons

The galleon emerged as a hybrid between the caravel and carrack. It retained the deep hull of the carrack but had a longer, narrower and lower profile, making it more manoeuvrable and seaworthy. Galleons featured multi‑deck gun ports, heavy cannons and a square tuck stern, giving them both cargo capacity and firepower. They dominated Iberian fleets from the 1560s onward. Spanish Manila galleons sometimes reached 2 000 tons, while most Portuguese galleons were smaller (often under 500 tons), allowing them to operate on the treacherous Cape Route to India. Galleons carried the silver, spices and Chinese silks that enriched the union. According to a recent study, Portuguese reliance on ever larger galleons during the union contributed to a high loss rate: nearly one in five ships (18.5 %) on the Cape Route were lost between 1601–1650, partly because large vessels were less seaworthy and more vulnerable to storms and enemy attacks.

(A technical drawing of a late 16th–early 17th century 500-ton Portuguese galleon from Livro de Traças de Carpintaria (“Book of Draughts of Shipwrightry”), compiled by shipwright Manuel Fernandes. The 500-ton rating denotes the vessel’s cargo capacity below the main deck under contemporary Portuguese regulations.)

East Indiamen and Naus da Índia

The Portuguese also built East Indiamen or nau da Índia, huge carracks specifically for the India trade. They could carry 600–1 600 people and massive cargo. Goods exported from Macau to Goa included Chinese silk, gold, musk, mercury, porcelain, sugar and camphor; returning ships brought silver, pepper, pearls, ivory and sandalwood, creating a profitable circular trade. Raw silk shipments alone increased from 270 000 taels of silver between 1580-1590 to 480,000 taels by 1635, reflecting the scale of the East Asian.

Spanish Galleons and Treasure Fleets

Spain organised its transatlantic trade into treasure fleets. Twice each year, convoys of galleons and smaller ships sailed from Seville to the Caribbean to collect silver and goods before returning to Europe. The convoys divided into the New Spain fleet to Veracruz and the Tierra Firme fleet to Cartagena and Portobelo. After loading silver, cochineal and other exports they regrouped in Havana and returned home. Spanish galleons were heavily armed and carried soldiers to deter pirates; nonetheless, storms and reefs were bigger dangers than enemy attacks. Another route – the Manila galleon – connected Manila to Acapulco. These annual galleons carried Asian goods like Chinese silk to Mexico and returned with Mexican silver and passengers; profits often reached 100–300 %.

Smaller Vessels: Lanchas, Chalupas and Patache

Spanish ports also used smaller vessels such as lanchas, chalupas and patache for coastal trade and communication. These ships, typically less than 30 tons, ferried supplies and passengers between larger ships and shore. The patache served as a dispatch boat for fleets and often accompanied galleons. Galleys with oars were employed for harbour manoeuvres or as escort craft. A contemporary description notes that Spanish galleons had both square and lateen sails and sometimes carried oars for manoeuvring, with crews of around 100 sailors, plus passengers and soldiers. These auxiliary vessels were vital for maintaining the empire’s day‑to‑day operations.

Warships and Naval Innovation

Galleons as Warships

Because they combined cargo capacity with heavy armament, galleons served as the principal warships of the Iberian Union. The Spanish Armada of 1588 contained twenty galleons and four galleasses, while the majority of vessels were armed merchantmen (naos) and smaller support vessels such as urcas, zabras, pataches, pinnaces and caravels. Portuguese-built galleons were also integrated into Castilian fleets; an academic study notes that Portuguese galleons initially formed the core of Spanish naval power, but from the late 1590s Spain provided galleons to Portugal as the union’s losses mounted.

Galleys and Galleasses

In addition to sailing ships, the union maintained fleets of galleys and galleasses, particularly in the Mediterranean and Atlantic coast. Galleys were long, narrow vessels driven by oarsmen; they could sprint in calm winds and were suited to coastal defence, troop transport and operations in confined waters. Spain maintained four permanent galley squadrons to guard its coasts and trade routes. These galleys ferried troops and supplies across the Mediterranean, Caribbean and even the Dutch campaigns, and they participated in the 1583 invasion of the Azores. Galleasses were hybrids combining sails and oars; they had higher freeboard and a gun deck, making them powerful but slower. A history blog notes that galleasses first appeared in the 1520s and remained popular until the early 17th century. They were used in the Mediterranean and Atlantic, rowed by slaves or convicts, and carried guns either above or below the oars. Venetian galleasses were large galleys with hulls similar to sailing ships; Spanish Atlantic galleasses were essentially sailing ships fitted with oars to manoeuvre in battle.

Naval Doctrine and the Convoy System

To protect commercial shipping from pirates and rival navies, both Spain and Portugal developed convoy systems. Spain’s treasure fleets were strictly convoyed and escorted by war galleons and galleasses. Portugal responded to Dutch and English privateers by organising its India fleets into armadas – heavily armed convoys of carracks and galleons guarded by galleys and galleasses. After the union ended, Portugal created the Brazil Company (1649) to organise sugar convoys; it also introduced convoy systems to protect shipping from privateers and Dutch raiders. Nevertheless, the Cambridge study reveals that Portuguese reliance on very large ships increased losses: only 3.8 % of voyages between 1601–1650 were lost to enemy attack, but the net loss rate rose to 14.7 % due to storms and over‑loading.

( Painted by Juan Bautista Maíno (1580–1649) in 1634-35. The painting commemorates the Spanish-Portuguese joint expedition that recaptured the Brazilian port of Salvador da Bahia (Bahía de Todos los Santos) from the Dutch in 1625.)

Trade Networks and Economic Foundations

Indian Ocean and East Asian Trade

The union inherited Portugal’s extensive Indian Ocean network. From Lisbon and Seville, fleets sailed around the Cape of Good Hope to Goa, Hormuz, Malacca, Macau and Nagasaki. The Dutch–Portuguese War article lists key fleets that controlled these routes: the Daman and Diu fleet, Sofala–Mozambique armada, Hormuz fleet, Malacca fleet (for the Straits of Malacca) and the Macau fleet for the route to Japan and China. Portuguese Macao served as the Far East’s primary entrepôt, linking Chinese goods with Europe. Its naus transported hundreds of people and goods like silk, gold, brass, musk and porcelain to Goa and Europe, returning with silver, pepper, pearls and raw silk exports from Macau to Goa were valued at 270 000 taels of silver annually between 1580–90, increasing to 480 000 taels by 1635. However, the Dutch capture of Malacca in 1631 disrupted this route, cutting off Goa from Macau and ending Portugal’s dominance in the Western Pacific.

Atlantic Trade and Brazil

Portuguese Brazil was the union’s most important colony. The colony’s economy revolved around sugar plantations, which required vast amounts of labour and capital. By 1570 there were sixty sugar mills; by 1645 there were 350 mills. To meet the labour demand planters imported large numbers of African slaves: between 1600 and 1625, about 150 000 African slaves were shipped to Brazil, and one-third of all slaves in the Atlantic trade were transported in Portuguese vessels. Sugar was shipped to Europe in convoys; profits from sugar surpassed those from pepper and spices. The union also exploited brazilwood, tobacco and, later, diamonds.

Competition was fierce. Dutch and English privateers targeted sugar shipments, and the Dutch West India Company captured Salvador (1624) and later Olinda and Recife (1630), renaming the territory New Holland. The union eventually expelled the Dutch after battles such as Guararapes, but only in 1654. Brazil remained Portuguese, but the conflict disrupted sugar production and trade. To regain prosperity, Portugal introduced the Companhia Geral do Comércio do Brasil (Brazil Company) in 1649 to organise trade and convoys; after independence from Spain in 1640, Portugal paid four million cruzados to the Netherlands to renounce claims on Brazil.

Transatlantic Slave Trade and the Caribbean

Slave-trading voyages were integral to the union’s economy. Portuguese and Spanish merchants transported enslaved Africans to Brazil and the Caribbean, where they worked on sugar and tobacco plantations. The union’s involvement in the slave trade is evident from the high mortality rates: about one in five enslaved people died during the voyage, highlighting the brutality of the trade. The Spanish Caribbean also relied on enslaved labour; the island of Hispaniola and port of Cartagena were major slave markets.

Silver and Global Commerce

Silver from the Americas financed the union’s wars and imports. The Spanish treasure fleets carried millions of pesos in silver and gold from Mexico and Peru to Seville. In the Pacific, the Manila galleon trade acted as a bridge between the Americas and Asia, carrying Chinese goods eastward and Mexican silver westward. Portuguese merchants used silver from Brazil and Spanish America to purchase spices and luxury goods in Asia. Yet the reliance on silver also exposed the union to piracy and storms; the loss of a single treasure fleet could devastate royal finances.

Exploration and Territorial Expansion

Continued Exploration of Asia and the Pacific

While the golden age of Iberian exploration occurred in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, exploration continued under the union. Portuguese navigators ventured inland in Brazil, exploring the Amazon and hinterland in search of minerals and indigenous peoples. Jesuit missionaries accompanied them, establishing missions deep in the interior. In Asia, the union inherited Portugal’s outposts and Spain’s possession of the Philippines. The Spanish Pacific empire was maintained through the Manila galleon, but there were few new long-distance discoveries. Instead, exploration focused on mapping and improving routes. The union also launched expeditions to Hokkaido and the Marianas to expand trade networks.

Dutch and English Challenges

The union’s maritime dominance provoked the rise of rivals. The English East India Company (1600) and Dutch East India Company (VOC, 1602) were chartered by their governments to break Iberian monopolies in the East Indies. Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius justified Dutch aggression with the concept of mare liberum (free sea), arguing that no nation could claim exclusive sovereignty over the ocean. Dutch fleets attacked Portuguese forts in the Indian Ocean and captured the rich Portuguese carrack Santa Catarina in 1603. They seized Malacca (1641), Ceylon (1658) and threatened Macau and Goa. English privateers and buccaneers harassed Spanish treasure fleets and sacked port cities like Cadiz and Veracruz. The intensifying competition eroded Iberian dominance and forced technological adaptation.

Decline and the Portuguese Restoration

Political and Economic Strain

The union strained Portugal’s resources. Portuguese merchants complained that Spanish monopolies and royal taxes diverted wealth to Castilian wars, such as the Thirty Years’ War, leaving Portuguese interests undefended. Habsburg policies made Spain’s enemies – England and the Netherlands – Portugal’s enemies, drawing the country into conflicts in which it had little stake. By the 1630s the spice trade was declining and Asia outposts were under siege; the sugar trade faced Dutch invasion; and the Portuguese nobility resented being governed from Madrid. High loss rates of ships on the Cape Route further reduced profits. These pressures culminated in the Restoration War (1640–1668), in which Portugal regained independence under the House of Braganza.

( 1630: Dutch siege of Olinda, located in the Brazilian captaincy of Pernambuco, the largest and richest sugar-producing area in the world. )

Legacy

By the time the union dissolved, Iberian maritime supremacy had waned. The Dutch and English had surpassed the Iberian powers in shipbuilding and commercial organisation, using smaller but more seaworthy ships and private capital to outcompete state‑run fleets. The union had nonetheless created a global network linking Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas, a maritime silk road that fostered cultural exchanges, carried missionaries and colonists, and spread plants and animals around the world. Its ships – caravels, carracks, galleons, galleasses and galleys – illustrate a period of intense experimentation and adaptation in naval technology. Trade convoys and treasure fleets financed empires but also invited piracy and conflict. Meanwhile, the exploitation of slave labour and indigenous lands underscores the human cost of Iberian expansion.

Conclusion

The maritime history of the Iberian Union between 1580 and 1640 is a story of innovation, ambition and decline. A unified Iberian monarchy briefly commanded the world’s most extensive trading networks. It employed a sophisticated array of ships: nimble caravels probing coastlines, capacious carracks bearing spices and silks, heavily armed galleons escorting treasure fleets, hybrid galleasses patrolling coasts and galleys ferrying troops. These vessels enabled global trade and imperial defence but also made inviting targets for rivals. As Dutch and English companies embraced market‑driven innovation and built smaller, more efficient ships, Iberian fleets suffered from outdated designs, high loss rates and mounting debts. Colonial economies such as Brazil prospered from sugar and slavery yet became battlegrounds for control. The union’s end did not sever the maritime connections it forged; instead, it marked the transition to a new era of global competition, where maritime power depended on private enterprise, technological agility and efficient organisation. Today, the legacy of Iberian maritime history is visible in the cultural and linguistic ties across continents and in the historical narratives of exploration and exploitation that continue to shape the world.